ASIAN AMERICANS

In the mid-1800s, the state of California, being concerned about Asian immigration, produced more legislation against Chinese immigrants than against African Americans. (The Union victory of the Civil War had halted slavery from expanding into the Western expansion, opening the door to immigrant labor for particularly dangerous, and low paying jobs.) Jim Crow laws were created to chip away at the civil right and liberties of Asian Americans, immigrants and anyone who wasn't white. From the 1850s until the 1960s, Jim Crow legislation attacked their rights to due process (the right to testify in court), which had the same effect as legalizing the murder of non-whites, since witnesses to those crimes could not legally testify in court. Jim Crow laws denied people of color their civil rights to hold office, vote, marrying a Caucasian (miscegenation), receive an education, employment, consume alcohol, and choosing where they live. Jim Crow laws also forced segregation.

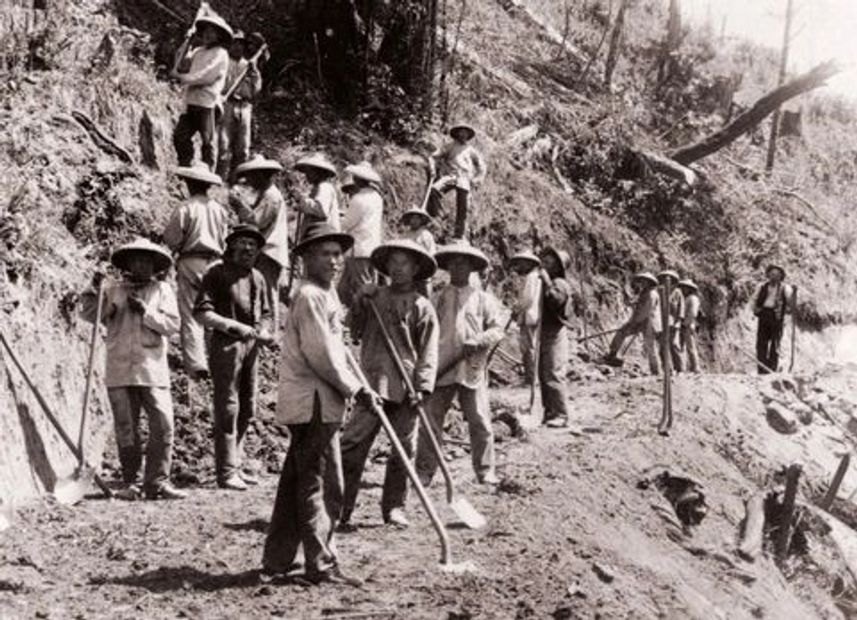

'By 1880, Chinese immigrants, brought in by the railroads to do the backbreaking labor at pitiful wages, numbered 75,000 in California, almost one-tenth of the population. They became the objects of continuous violence. The novelist Bret Harte wrote an obituary for a Chinese man named Wan Lee:

Dead, my revered friends, dead. Stoned to death in the streets of San Francisco, in the year of grace 1869 by a mob of halfgrown boys and Christian school children.

In Rock Springs, Wyoming, in the summer of 1885, whites attacked five hundred Chinese miners, massacring twenty-eight of them in cold blood.'

- A People's History of the United States, by Howard Zinn.

Like California, many other states had anti-miscegenation laws targeting Asian groups, making it illegal for them to marry white partners. The Expatriation Act was struck down by the Cable Act of 1922, but still maintained that women who married "aliens ineligible for citizenship" (Asian men) would still lose their citizenship.

In Februrary 1942, after the Pearl Harbor attack, Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 giving the army the power, without warrants or indictments or hearings, to arrest all 110,000 Japanese Americans on the West Coast. Men, women and children were taken from their homes, forced into relocation and incarcerated under armed guards for over three years. Their homes, businesses and property were seized and never returned.

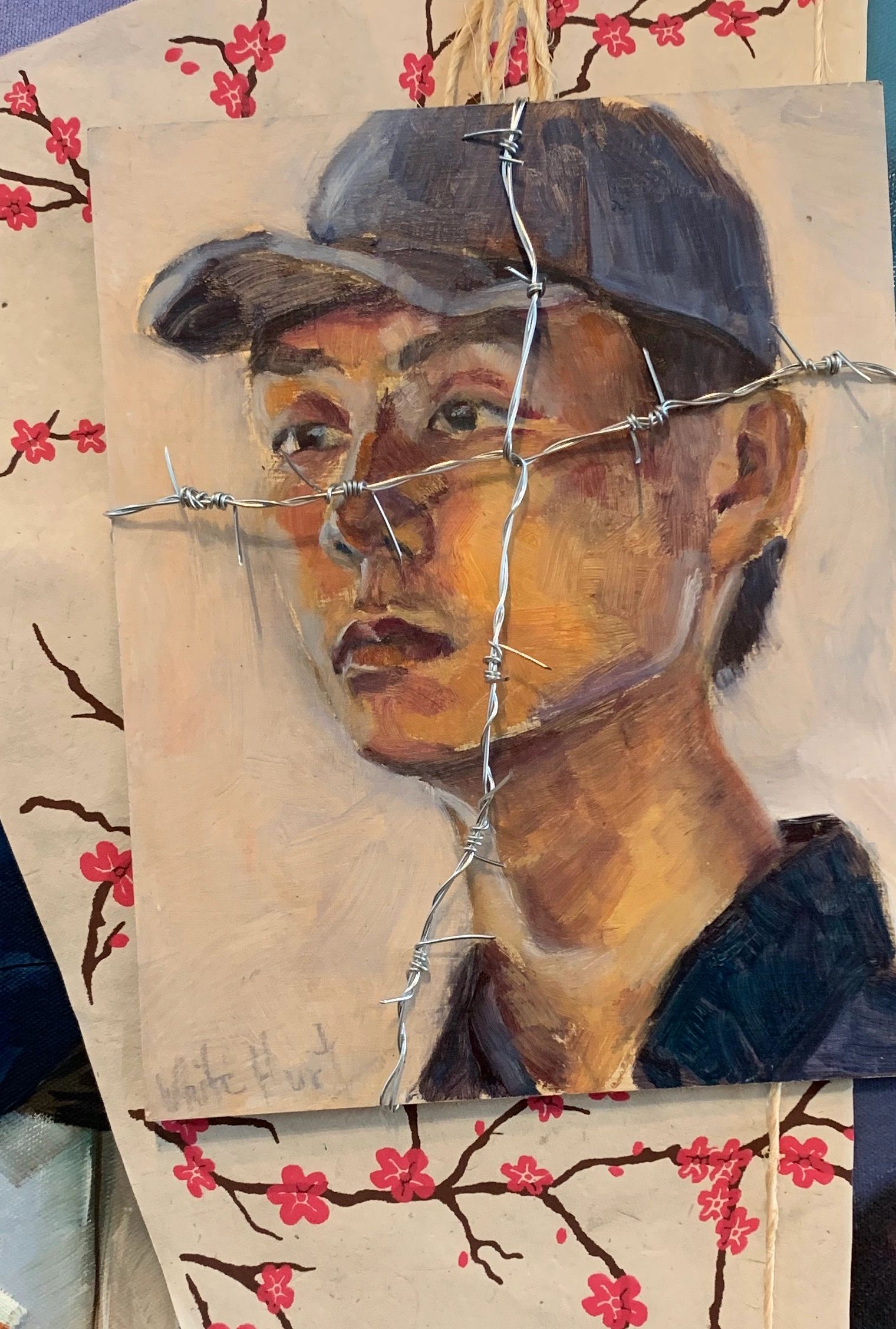

Photo: Detail of:

US History (forgotten).

Oil on canvas and mixed media.

Japanese Internment Stories

The Hagiwara Family

The Hagiwara Family

The Hagiwara Family

A family at the heart of San Francisco Golden Gate Park's beloved Japanese Tea Garden.

The Tanaka Family

The Hagiwara Family

The Hagiwara Family

Did not learn of family's internment until 9 years of age.

JIM CROW LAWS IN CALIFORNIA 1850s - 1960s

edogamy - restricting marriage to people within the same caste. (Outlawing marriage between whites to Blacks, Asians or Native Americans.) Forty-one of the fifty states passed laws making intermarriage a crime punishable by fines of up to $5000 and up to 10 years in prison. Some states went so far as to forbid the passage of any future law permitting intermarriage. Outside of the law, particularly in the South, African-Americans faced penalty of death for even the appearance of breaching this pillar of caste. The Supreme Court did not overturn these prohibitions until 1967. Alabama did not throw out its law against intermarriage until the year 2000. Even then, 40 percent of the electorate in that referendum voted in favor of keeping the marriage ban on the books. - Caste, Isabel Wilkerson

California targeted Asian immigrants and all people of color with laws restricting: due process, holding office, employment, voting, residence, miscegenation (marriage to a Caucasian), education, alcohol, where they could live and forced segregation.

In the state of California, concern about Asian immigration produced more legislation against Chinese immigrants than against African Americans.

1854: [Due Process] Supreme Court of California precluded persons of Chinese descent from testifying for or against a white man.

1854: [Holding Office] California’s constitution stated that “no native of China” shall ever exercise the privileges of an elector in the state.”

1866-1947: [Segregation, Voting, Miscegenation, Education, Employment] San Francisco city ordinance required all Chinese inhabitants to live in one area of the city. A San Francisco a miscegenation law passed in 1901 was broadened in 1850, adding it unlawful for white persons to marry “Mongolians.”

1860 – 1880; 1885: [Education] Children of “Negroes, Mongolians, and Indians” must attend separate schools. In 1870 the requirement to educate Chinese children was dropped entirely and separate schools were repealed in 1880 but reestablished for Chinese students in 1885.

1872: [Alcohol] Sale of liquor was prohibited to Indians. {Repealed in 1920.}

1879: [Voting] “No native of China” would ever have the right to vote in the state of California. Repealed in 1926.

1879: [Employment] Public bodies were prohibited from employing Chinese and called upon the legislature to protect “the state…from the burdens and evils arising from” their presence. [This anti-Chinese state referendum was passed by 99.4% of voters in 1879.}

1880: [Miscegenation] Statute made it illegal fro white persons to marry a “Negro, mulatto, or Mongolian.”

1890: [Residential, Segregation] San Francisco’s Bingham Ordinance ordered all Chinese inhabitants to move into a certain area of the city within six months or face imprisonment. {Later found to be unconstitutional by federal judge.}

1891: [Residential] All Chinese required to carry with them at all times a “certificate of residence” or be arrested and jailed.

1894: [Voting] Any person who could not read the Constitution in English or write his name would be disfranchised. {Nearly 80 % of voters support an educational requirement.}

1901: [Miscegenation] The 1850 law prohibiting marriage between white persons and Negroes or mulattoes was amended, adding “Mongolian.”

1909: [Miscegenation] Persons of Japanese descent were added to the list of undesirable marriage partners of white Californians as noted in the earlier 1880 statue.

1913: [Property] “Alien Land Laws” prohibited Asian immigrants from owning or leasing property. {Struck down by California Supreme Court in 1952.}

1931: [Miscegenation] State code prohibited marriages between Caucasians and Asians.

1933: [Miscegenation] State code broadened to also prohibit marriages between whites and Malays.

1945: [Miscegenation] Statute prohibited marriage between whites and “Negroes, mulattos, Mongolians and Malays.”

1947: [Miscegenation] Subjected rigorous background checks on U.S. servicemen and Japanese women who wanted to marry. Barred the marriage of Japanese women to white servicemen if they were employed in undesirable occupations.

Chinese Immigrants Building US Railroads

Anti-Miscegenation Laws

Mixed-race marriages still illegal in these states in 1940s:

Arizona - Asians, Filipinos, Native Americans

California - Asians, Filipinos

Idaho - Asians

Maryland - Filipinos

Mississippi - Asians

Missouri - Asians

Montana - Asians

Nebraska - Asians

Nevada - Native Americans, Asians, Filipinos

Oregon - Native Americans, Asians, Hawaiians

South Carolina - Native Americans, Native Americans

South Dakota - Asians, Filipinos

Utah - Asians, Filipinos

Virginia - All non-whites

Wyoming - Asians, Filipinos

In the aftermath of World War II, politicians stressed the importance of the US's image as the leading democratic nation in the fight to combat Communism. While stationed in Japan and Korea, American GIs frequently married foreign women, especially Asian ones. Politicians needed to develop laws for GIs to bring their foreign wives back to the US, despite the existence of national origins quota laws and anti-miscegenation laws. The movement towards accepting Asian women was evident by the passage of new laws, namely The War Brides Act of 1945. The War Brides Act allowed for the immigration of Asian war brides to the United States under a non-quota bias, undermining state and local anti-miscegenation laws. Importantly, Asians were not included in national origins quota admittances, instead falling under “Asiatic Bar Zone” which totally restricted Asian immigration. As a result, 80% of the Japanese immigrants in the 1950 came to the US as wives of US soldiers. The Immigration Act of 1924 remained a working law until 1952, when Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act.

The Hagiwara Family's Story

Japanese American family at heart of beloved Golden Gate Park garden By Meyer Gorelick

Feb. 15, 2020 - The Japanese Tea Garden, the oldest public Japanese garden in North America, is a popular attraction with tourists and locals alike.

But few know that it was once also home to the man who designed it and his family — or that they were abruptly removed at the start of World War II and interned along with thousands of other Japanese Americans.

This month, as Recreation and Parks officials prepared for a $2 million spring renovation of the garden and its pagoda to celebrate its 125th anniversary, members of that family returned to the garden to talk about that dark chapter in its history and the man who helped create it.

Tanako Hagiwara was 4 years old when her family was relocated from their 17-room home in the garden, first to a camp at Tanforan in San Bruno, and later to Topaz Internment Camps.

Hagiwara, 81, has no specific memories of the garden or her internment, just vague recollections of the places. She remembers her childhood home that was torn down months after they left for Tanforan and replaced with a European-style sunken garden. She also remembers more bleak surroundings from her Topaz detention center.

“I remember the barbed-wire fences and sage brush, and all that kind of stuff,” Hagiwara said.

The family’s removal erased three generations of Hagiwara blood, sweat, tears and belongings.

A friend of Golden Gate Park Superintendent John McLaren, Makoto Hagiwara took over as manager of what had been the “Japanese Village,” an exposition for the 1894 World’s Fair that at the fair’s conclusion was converted into the Japanese Tea Garden.

Despite his removal as manager in 1901 due to an anti-Asian immigrant amendment to the city charter, Makoto Hagiwara continued acting as a shadow architect and planner for the Japanese Tea Garden, carrying out his plans for the garden while he opened and operated a competing garden blocks away.

By 1906 he had been restored as manager by the Board of Supervisors, and in 1909 he built his family home in the garden. He continued expanding and improving the garden until his death in 1925.

The garden’s pagoda, exhibited during the 1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition in the Marina District, was moved at the exposition’s conclusion to the Japanese Tea Garden.

Dawkins, Tanako Hagiwara’s son, said he didn’t learn much about his family history until a ceremony in 1974, when local sculptor Ruth Asawa designed a plaque in the garden commemorating the contributions the Hagiwaras made to San Francisco.

“I didn’t know anything about it until I was about 12 or 13 years old,” Dawkins said, adding, “I actually became maybe more interested in the garden than my mother.”

Dawkins has since become a family historian of sorts and maintains connections with the current garden staff.

The destruction of their family home and the attack on Japanese-American culture that ensued in 1942 were no doubt traumatic to the Hagiwaras, but Dawkins and his mother harbor positive feelings toward the garden. For one thing, it’s still here. Chicago’s Japanese garden was burned to the ground in anti-Japanese fervor at the outbreak of the war.

While the garden was rebranded as the “Oriental Garden,” and lost multiple buildings during the war, Dawkins said San Francisco could have done a lot worse. Many of the Hagiwaras’ possessions, after negotiations with The City, were relocated to the home of family friend Samuel Newsom in Mill Valley. In the 1950s, however, many of those items were auctioned off. The proceeds were used to make a down payment on the home in the Richmond District that Tanako Hagiwara lives in today. Tanako Hagiwara was a central figure in the City College of San Francisco women’s athletics department and continues working for the school part-time as an older adult educator.

“I taught every class except martial arts and football,” she said.

Steven Pitsenbarger, gardener captain at the Tea Garden, has attempted to restore the elements of Japanese culture that were lost during WWII. “We have the weight of being more than just a garden,” said Pitsenbarger, who wants to maintain Makoto Hagiwara’s goal of giving visitors an authentic taste of Japanese horticulture. The six- to nine-month renovation will be fully underway in April and improvements to the pagoda, which is in poor condition, are expected to begin as soon as next week.

By Meyer Gorelick of The San Francisco Examiner

The Japanese Tea Garden in San Francisco's Golden Gate Park

The Tanaka Family's Story

A Story of Japanese American Internment By Lani Miki Tanaka

March, 2020 - I am Lani Miki Tanaka. I was born in 1961 in Los Angeles. My father was Michio Mickey Tanaka born in Santa Monica, California in 1928. My mother was Mildred Midori Kawasaki Tanaka born in Lanai, Hawaii in 1934. My father’s parents came from Maui, Hawaii. My grandparents were Henry Tanaka and Alice Nakamura Tanaka.

The story is that my grandfather told my grandmother that he was going to the mainland to seek his fortune and that he would be back for her in a year. They would get married and move to the mainland. And so he did and they did.

I learned about the internment, I think in about 3rd grade history. I had a very progressive teacher. We studied “Afro Americans” and also first learned about what the government did to the Japanese Americans on the west coast. Reading about it in my history book brought instant shame. I was the only Japanese kid in my class. I did the math and realized that my dad’s parents, my dad and my uncle must have all been interned. They had never talked about it. I confronted my father that evening at dinner. He started to tell me stories about it. He had fond memories of the internment. He was only around 13 years old. Manzanare is also where he met George Nojima his oldest and best friend.

Growing up we went on yearly fishing vacations up the coast sometimes all the way to Vancouver, with the Nojimas. We often stopped at a place Uncle George and my dad called “camp” to take pictures. It was weird because there wasn’t much there. This was before any memorials were built on the site. At that time there was a sort of dilapidated watchtower and some barbed wire.

My grandmother on the other hand hated Manzanar. It was terrible. She really hated the food and the way they lived. Also, she was bitter that my grandfather, without telling her sold the family business, “Tanaka’s Produce” on Montana Blvd. in Santa Monica a year before the war ended. She was especially mad because they had just put in expensive refrigeration before the internment.

My grandfather was in Arizona most of the war. He was in a hospital. My Uncle Eddie, who was older than my dad apparently toured the Midwest with his band. I have only seen a picture of him playing the guitar in a cowboy hat. In front was a dancing girl in a hula skirt. My mom was very young during the war. Since she was in Lanai an island of over 900 Japanese and an overall population of around 3200. So, the Japanese were not interned but had a curfew.

Lani Tanaka's Grandmother.

'This is my grandmother. I think she was 15 here. That's when she got married. My grandfther was in his 30's. Men married late because it took them a while to get settled and work enough to support a wife.'

- Lani Miki Tanaka

Lani Tanaka's Grandfather.

'This is my grandfather. He drove the workers to the harbor to load the pineapple barge. (The Hawaiian Pineapple Co., Lanai City, Hawaii) The story is that he came from Japan with somebody else's name that wasn't able to come at that time to Hawaii. Hawaii was only a territory but still had the quota.'- Lani Miki Tanaka

Aiko Herzig Yoshinaga : She brought Justice for Japanese-Am

By Maggie Jones (New York Times Magazine)

AIKO YOSHINAGA WAS 17 when her high school principal called her and 14 other Japanese-American students into his office. It was April 1942 in Los Angeles. Yoshinaga was an honors student, two months from graduating, with dreams of college and becoming a dancer and a singer. The principal had other ideas. “You don’t deserve to get your high school diplomas,” Yoshinaga recalled him saying, “because your people bombed Pearl Harbor.”

Earlier that year President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, creating the path to imprison more than 110,000 Japanese-Americans who lived on the West Coast. Government officials would claim it was a “military necessity” to create “internment camps,” as they were known. Some military leaders used perkier euphemisms: “relocation centers,” “wayside stations,” “temporary homes,” “havens of rest and security.”

Yoshinaga arrived that spring in the “wayside station” in Manzanar, Calif., 250 miles from home. When she stepped off the bus, she saw armed soldiers. Maybe they’ll shoot us, she thought to herself; no one would even know. Officials ordered Yoshinaga to fill a sack with hay for her bed and go to her assigned barrack. She shared one room with her new husband and five of his family members. (Yoshinaga had eloped rather than separate from her high school sweetheart; her parents ended up in a camp in Jerome, Ark., 1,800 miles away.) The room had a single bulb, a stove, some cots and blankets. No running water, no kitchen. The hastily constructed wood walls invited sand and dirt during dust storms, biting winds in the winter.

The next year, Yoshinaga gave birth to her first child at Manzanar in a hospital ward she shared with half a dozen other women moaning in labor. Then, after months of waiting for permission to visit her ailing father, she and her infant daughter traveled by train for five days, most of them spent sitting on her suitcase, to arrive just before his death.

After the war ended, Yoshinaga received $25 and no clues on how to reassemble her life. For the next decades, she was too consumed by survival to dwell on the injustices she and her family had faced. It wasn’t until the late 1960s, after she’d divorced, remarried, divorced again and raised three children as a single mother, working various clerical jobs, that she joined the activist group Asian Americans for Action.

If you want to understand our history, the Japanese-American activist and writer Michi Weglyn told her, go to the archives. And so Yoshinaga did, initially focusing on her family’s history in the prison camps. But one set of documents in the National Archives in Washington led to others. And one to two days a week turned into five and six, up to 12 hours a day, sometimes accompanied by her third husband — her true love, as she would say — Jack Herzig, a former Army paratrooper.

Aiko Herzig Yoshinaga, as she was known after her marriage, stood all of five feet tall, with softly curled hair streaked with gray and Jackie O. eyeglasses the size of saucers. She dressed practically, slacks and sweaters, for her days in the wood-paneled reading room, a cart by her side filled with boxes from the stacks. She brought a purse, a brown-bagged lunch and her own copy machine. And, document by document, she took poorly indexed artifacts from the War Relocation Authority and other government agencies and read, copied and knit them together in her mind and in her meticulous filing system cross-referenced by date, location and subject.

In 1981, she applied to be a researcher with the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, created by Congress to uncover the motives behind Executive Order 9066 and to document its impact. By then, Herzig Yoshinaga had already accumulated about 8,000 documents. Her two-bedroom apartment had sprouted filing cabinets and cardboard boxes stacked five and six high. A bathtub became a repository. The dining-room table disappeared under copies of internal memos, cables, war reports.

Then one day in 1982, she picked up a 6-by-9-inch black book from the corner of an archivist’s desk. It looked much like the 1943 published report by Gen. John DeWitt, who proposed and oversaw the evacuation of Japanese-Americans during the war. But the one in Herzig Yoshinaga’s hands was a bit smaller and not bound at the spine. As she flipped the pages, she saw pencil markings around sentences that never appeared in the final report. The War Department had long claimed the military lacked time to hold hearings to distinguish loyal Japanese-Americans from the disloyal ones (in fact, no incident of espionage by Japanese-Americans was ever uncovered). In this version of the report, though, DeWitt acknowledged that time had nothing to do with his plan. Instead, he wrote, it was “impossible” to distinguish one Japanese-American from another. The military would never be able to separate “the sheep from the goats.”

Herzig Yoshinaga already knew that Peter Irons, a lawyer with whom she later collaborated as he sought to reverse wartime convictions of Japanese-Americans, had uncovered records showing that War Department officials had insisted on revisions to DeWitt’s original report, because it countered their public rationale for imprisoning Japanese-Americans. She knew, too, that the department had ordered all copies destroyed. But one copy, she remembered, had gone missing. Now it was in her hands. “I nearly hit the ceiling,” Herzig Yoshinaga said later, describing that day.

Her finding became key evidence in the commission’s report, "Personal Justice Denied," published in 1982 and ’83. It concluded that the “internment” was based on “race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership.” (Herzig Yoshinaga pushed the commission, and later the public, to use the term “concentration camps” to describe the experiences of Japanese-Americans, a majority of them United States citizens, imprisoned without cause or trial, behind barbed wire, surrounded by watchtowers and armed guards.)

The report led to President Ronald Reagan’s issuing an apology in 1988 and to restitution payments of $20,000 for each survivor. Herzig Yoshinaga’s discovery also helped Irons and his co-counsel Dale Minami in their 1983 successful effort to overturn the criminal conviction of Fred Korematsu, a welder who had defied orders to report to an “internment center,” as well as those of Gordon Hirabayashi and Minoru Yasui in similar cases. (In 1944, Korematsu unsuccessfully challenged Roosevelt’s executive order before the Supreme Court. It wasn’t until last year that the court agreed that Americans cannot be forcibly relocated on the basis of race.)

Despite the victories, wounds remained. Among those for Yoshinaga and some of her high school classmates was the one inflicted by their principal. One former student asked the Los Angeles school board — whose members included Yoshinaga’s son-in-law, Warren Furutani — to make amends. And so, one October Saturday in 1989, Yoshinaga and about a dozen of her classmates, all in their 60s, stood inside Los Angeles High School in optimistic blue caps and gowns, with pinned carnations. They listened to an apology from the school board. A classmate led them in the old school cheer. And they walked one by one across the stage for their diplomas. The date on those diplomas was June 26, 1942. That was the day that, in a different atmosphere, under different political leadership, each one of them would have stepped out into a new life. One filled with choices and with freedoms.

]