Venus Degentium (Venus Diaspora)

Collage by M Susan Broussard

The fifth of the Venus Series collages, Venus Degentium (Diaspora Venus), represents the African diaspora (separation from ancestral homeland). The figure and face of this Venus celebrates African femininity, in contrast to the classical Greek and Roman feminine ideal. Her long curly hair is made from a collage of the United States. She stands regally upon an open book (truth and knowledge) / lotus flower (serenity) / half-shell (beauty). The two-page spread shows a map of the world misleadingly entitled, “The Age of Discovery”. She is unchained, but the pages of the book are bound together with chains which represents our inescapable tie to our nation’s history. She wears a halo in homage to generations of suffering and martyrdom as a result of the slave trade. In her hand she holds the continent of Africa in a loose grip.

collage of paper 2023

36 x 24 in (91 x 61 cm)

RECONSTRUCTION: After the Civil War, 1862 - 1877

Emancipation without Freedom: Jim Crow & Black Codes

Reconstruction marks the period after the Civil War. The aim was to reconstruct a country that had been torn apart by war. In this case, the word reconstruction sounds deceptively positive and hopeful. The war's Union victory, along with the abolition of slavery and three Constitutional Amendments might suggest that the moral issue of slavery had finally won out. Instead, more people died in political violence from 1862 to 1900 than in any other peacetime era in US history. A purgatory of terror and shame, every bit as dark a stain as slavery, describes life between the Civil War and civil rights movement. Some civil rights issues continue to this day.

For many years leading up to the Civil War, the institution of slavery had dominated the economic, political and social life in both the former Confederate states, and some of the northern states. It is wrong to assume that with emancipation and the legal end of slavery the playing field was magically leveled, and the former slaves were simply granted citizenship, equality and freedom. Political and legal change proved substantially easier to enact than social change. The signing of The Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 may have freed 4 million slaves, but emancipation came without actual freedom. Some slaves would not learn for years that they had been emancipated. For a short period, Union troops remained in the South to enforce The former Confederate states bitterly refused to accept defeat or play fair, and succeeded at preserving slavery-like conditions for the next century. These ex-Confederate states found and exploited every loophole to undermine each piece of Reconstruction legislation intended to grant emancipation, citizenship and the right to vote. White landowners did their best to prevent a free-market system from replacing slave labor, diabolically creating a labor force system that was very similar to plantation slavery. Black Codes and "Jim Crow" laws targeted newly freed slaves, denying them the ability to assert their independence and gain economic autonomy.

In 1865, Mississippi and South Carolina were the first states to enact Black Codes. Mississippi's law required former slaves provide written evidence of employment for the coming year every January. If they stopped working that job before the end of the contract, their earlier wages would be forfeited, and they would be subject to arrest.

The US's first prisons-for-profit forced newly freed slaves to work against their wills. It was very lucrative for the states, to rent out chain gangs of prisoners, forcing them to work on plantations without being paid, just like slaves. Only conditions could be harsher and more violent than during slavery, because a slave's life had financial value. Many chain gang workers were literally worked to death or beaten to death.

Having control of the legislative bodies at a regional level, most all of the former Confederate states passed strict vagrancy and labor contract laws, as well as so-called “anti-enticement” measures. Vagrancy laws made it illegal to be homeless or jobless, which is expected and normal behavior for freed slaves. Prisoners were rented out against their will, and forced to labor without being paid, like in the days of slavery.

"Anti-enticement" Measures benefited white employers at the expense of black workers, and were designed to punish anyone who offered higher wages to a black laborer already under contract.

In South Carolina, it was illegal for Blacks to work in any occupation other than farmer or servant unless they paid a tax of $10 to $100 yearly. The former Confederate states passed strict vagrancy and labor contract laws. It was illegal to be homeless or jobless, "vagrant", which would be normal and expected behavior for freed slaves. Those arrested for vagrancy were often forced to work on chain gangs like slaves.

Not until the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1963 were these anti-Black laws finally abolished.

The term "states rights" may pop up in textbooks as one of the primary causes of the Civil War. The former Confederate states may have lost the Civil War, but these individual states used loopholes to try to continue things in an antebellum manner. States wrote Black Codes and "Jim Crow laws" for nearly a century after the Constitution abolished slavery.

With the arrival of the first colonists, in lieu of due process and legal trials, lynchings by mobs had been commonplace. After the war ended, Black Americas became the most frequent lynching victims. Violence and barbarity directed towards African Americans and Native Americans continued to plague our nation like a cancer. The Native American genocide which had started with Christopher Columbus, continued at full force.

Abraham Lincoln became president in 1861. A year later, the crowning achievements of his presidency came with his signing of the Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862 and the passing of the 13th Amendment, freeing nearly 4 million slaves. Although Confederate states chose to ignore these legislation, until forced to do otherwise.

Lincoln's prematurely shortened term was marked by violence on many fronts. A year after becoming president, Lincoln ordered 38 Dakota Sioux men to be hanged. On December 26, 1862, the day after Christmas, showing our nation's taste for violent crimes against humanity, four thousand spectators crowded to gleefully view the largest mass execution in US history.

Two and a half years later, on April 8, 1865, the day before the Civil War ended with a Union victory, the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution freed nearly four million slaves. Five days after the Civil War ended Lincoln was shot. Vice President Andrew Johnson assumed the presidency on April 15, 1865.

The moral issue of slavery was never a concern of the Civil War. The war had been fought over slavery, but only to iron out certain economic details of the slave trade, where slavery could expand to, and who got political control of the slavery system.

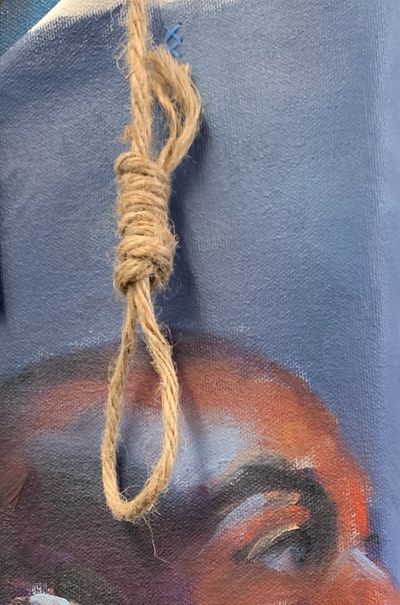

Photo: detail of "US History (forgotten)".

Oil on canvas and mixed media.

"The First Colored Senator and Representatives"

Short-lived hope of healing

Now that the war was over, the greedy quest for wealth and more Native American land continued. Some northerners wanted white colonists alone to make their fortunes building the western expansion, and did not want to see African slaves, Native people or immigrants to profit from it. Some northerners felt slavery was too unstable and unreliable a labor force to rely on for the rapidly growing industrial economy. Mostly northerners believed that because of slavery's violence, and since the life expectancy of slaves was greatly shortened, and slaves wanted to run away, it was not suitable for moving forward with the industrial age in the western expansion and the building of the transcontinental railroad. Some northern states made laws forbidding slaves to be transported through their states. The Southern slave states disagreed and resented these restrictions. Southerneres wanted to expand the slave trade into the west.

Southern states licked their wounds, and bitterly resumed violence against the newly freed African slaves, doing everything in their power to rig the system to deny them of their freedom, and to cheat them into laboring in near slave conditions.

When the Civil War ended, the Southern states were not automatically readmitted to the Union. Reconstruction Acts passed after the war applied to the former Confederate states (the Democrats) and did not apply to the North (The Republicans; although, not all northerners were anti-slavery.)

Voting rights for freed blacks proved a big problem. Reconstruction Acts called for black suffrage in Southern states (but not north). 11 of 21 northern states did not allow Blacks to vote.

One-sixth of the nation’s blacks resided in border states, and most of these states did not allow Black vote. (See slide show of Reconstruction Map on this page of website.)

The 15th Amendment was drafted between election day and Ulysses S. Grant’s inauguration on March 4th, 1869. (Grant had been the 6th Commanding General of the US Army during Abraham Lincoln’s presidency.) Congress was presented with three different versions. (The writers produced three as the writers were determined to pass the amendment.)

The 1st draft: Prohibited states from denying citizens the vote because of: race, color or having been a slave

The 2nd draft: Prohibited states from denying citizens the vote based on literacy, property, or the circumstances of their birth.

The 3rd draft: Stated plainly and directly that all male citizens who were 21 or older had the right to vote.

The first version, the most moderate of the three, was ultimately accepted. But many Congressmen felt that it did not go far enough, leaving too many loopholes.

Although Congress passed the 15th Amendment on February 26, 1869, some states resisted ratifying it. 17 Republican states approved ratification, and four Democratic states rejected it. In order to get the 11 votes needed to ratify it, Congress ruled that in order to be let into the Union, Southern states had to accept both the 15th and 14thAmendments. (On July 9, 1868, the 14th Amendment granted citizenship to all people born in the US, including former slaves.) The Southern states unhappily agreed to ratify the amendments in order to restore their statehood.

Many whites still refused to accept Blacks as their equals. As many had predicted, Southerners took full advantage of the Reconstruction Amendments’ loopholes to strip African Americans of their voting rights, keeping former slaves in near slavery conditions. In some instances, conditions were even worse than during slavery, because Black American lives were no longer valued as “property”.

Between 1885 and 1908, all 11 post-Confederate states passed Jim Crow laws establishing poll taxes, literacy tests, property and residency requirements and other measures aimed at stripping African-Americans of their voting rights. Some of these issues had been anticipated in the second and third drafts of the 15thAmendment, but were not passed by Congress. These Jim Crow laws and Black Codes locked in Democratic Party dominance and maintained near-slavery conditions, denying Black Americans of their Constitutionally given right to vote, as well as other civil rights. These measures, coupled with terrifying anti-black violence killed the dream of reconstruction. As Democrats and Republicans clashed over the rights of former slaves, white supremacist vigilante groups like the Ku Klux Klan gained strength.

These Jim Crow measures successfully achieved their goal: Black voter turnout in the South fell from 61 percent in 1880, to 2 percent in 1912 . In some states, laws forced freed slaves to accept minuscule pay. And if a black man was caught without a job, he could be charged with vagrancy. The courts would find him a job and force him to work it - but now they wouldn't have to pay him for his work.

Now that the Union and Confederate forces were no longer fighting one another, the uninterrupted focus of the US Army could return to stealing ancestral land from native Americans, often by means of genocide.

The US Senate signed the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty with the Sioux Nation promising they could retain their ancestral land in perpetuity. Three years later, when gold was discovered there, the US broke this treaty. Tensions escalated until 1890, when the US Army massacred three hundred unarmed men, women and children at Wounded Knee, then dumped their bodies in one mass grave. Fast forward to 1927: A nearby mountain range that natives called, The Seven Grandfathers, was carved and renamed, Mt. Rushmore. The faces carved into the Black Hills are those of four white men who contributed to the forced removal and extinction of native Americans from their ancestral land.

In 1870, five years after emancipation, the Fifteenth Amendment would allow some men who had been enslaved the right to vote. [Women would not be allowed to vote until 1920, fifty years later.] Southern states bitterly raised barriers to voter registration, which resulted in the disenfranchisement of most black voters, as well as many poor white voters. Poll taxes, grandfather clauses, literacy tests, requirements to own property, white primary elections (only allowing white voters), not to mention violent intimidation, resulted in the suppression of black participation.

The three Reconstruction Amendments were often ignored, particularly in the South. (Emancipation without freedom.) As freed slaves, the lives of black Americans now had even less value, and violence often increased, since they were no longer property with a monetary investment to protect. From coast to coast, Jim Crow laws were diabolically written to flagrantly deny freed slaves and immigrants of their rights. The questions still being debated were: who was an American, what rights should all Americans enjoy, and what rights would only some Americans possess. But the word "debated" makes it sound more civil than it was.

True equality and the same human rights as white Americans have never been granted to Black Americans, even to this day. Ancestral land and valuable natural resources continue to be stolen from native Americans.

Some of the most basic US history, which I was never taught in school, would have explained today's Black Lives Matter movement, why monuments of slave owners are being torn down, and why African Americans "can't just forget about slavery". It also explains centuries of crimes against Native Americans, including the Osage murders, today's Keystone pipelines and Mt. Rushmore. Until fairness, true equality and human rights are given to all, as a nation, we can not "just get over it" and begin to heal.

Union, Confederate & seceded states

Deciphering which bordering states were Union or Confederate, and which seceded is complicated. This slideshow of maps explains the timeline leading up to the Civil War, and until Reconstruction: 1861 - 1865.

Jim Crow Laws

15th Amendment / Jim Crow / Black Vote

Voting rights for freed Black Americans proved a big problem. Reconstruction Acts called for black suffrage in Southern states (but not north). Eleven of the twenty-one northern states did not allow Blacks to vote. One-sixth of the nation’s blacks resided in border states, and most of these states did not allow Black vote. (See slide show of Reconstruction Map on this page of website.)

With the end of the Civil War, the former Confederate states were not automatically readmitted to the Union. Reconstruction Acts passed after the war applied to these states, but did not apply to the northern (Union) states.

The 15th Amendment was drafted between election day and Ulysses S. Grant’s inauguration on March 4th, 1869. (Grant had been the 6th Commanding General of the US Army during Abraham Lincoln’s presidency.) Congress was presented with three different versions. (The writers produced three as the writers were determined to pass the amendment.)

The 1st draft: Prohibited states from denying citizens the vote because of: race, color or having been a slave

The 2nd draft: Prohibited states from denying citizens the vote based on literacy, property, or the circumstances of their birth.

The 3rd draft: Stated plainly and directly that all male citizens who were 21 or older had the right to vote.

The first version, the most moderate of the three, was ultimately accepted. But many Congressmen felt that it did not go far enough, leaving too many loopholes.

Although Congress passed the 15th Amendment on February 26, 1869, some states resisted ratifying it. 17 Republican states approved ratification, and four Democratic states rejected it. In order to get the 11 votes needed to ratify it, Congress ruled that in order to be let into the Union, Southern states had to accept both the 15th and 14thAmendments. (On July 9, 1868, the 14th Amendment granted citizenship to all people born in the US, including former slaves.) The Southern states unhappily agreed to ratify the amendments in order to restore their statehood. But many whites still refused to accept Blacks as their equals. As feared, Southerners took full advantage of every loophole of the Reconstruction Amendments in order to strip former slaves of their voting rights, and keep them in near slavery conditions. In some instances, conditions of the newly freed slaves were even worse than during slavery, because Black American lives were no longer valued as “property”.

Between 1885 and 1908, all 11 post-Confederate states passed Jim Crow laws establishing poll taxes, literacy tests, property and residency requirements and other measures aimed at stripping African-Americans of their voting rights. Some of these issues had been anticipated in the second and third drafts of the 15thAmendment, but were not passed by Congress. These Jim Crow laws and Black Codes locked in Democratic Party dominance and maintained near-slavery conditions, denying Black Americans of their Constitutionally given right to vote, as well as other civil rights. As Democrats and Republicans clashed over the rights of former slaves, white supremacist vigilante groups like the Ku Klux Klan gained strength.

By Jason Phillips, Ph.D., Mississippi State University

Presidential Reconstruction, 1865-1867

In May 1865, a month after the end of the American Civil War and the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, new U.S. President Andrew Johnson issued guidelines for re-admittance of the former Confederate states into the Union based on the Reconstruction plans that Lincoln had developed during the war. The president offered amnesty to individuals who would take an oath of loyalty to the United States, but there were exceptions. Confederates who had held high civil or military offices during the war and those who had owned property worth $20,000 or more in 1860 had to apply individually for a presidential pardon. When 10 percent of the voters in a state had taken the oath of loyalty, the state would be permitted to form a legal government and rejoin the Union. In Mississippi, Johnson appointed William L. Sharkey, a Union Whig, as provisional governor to guide Reconstruction in the state and to organize an election of delegates for a state constitutional convention.

Colonel Samuel Thomas, the assistant commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau who opened the Bureau office in Vicksburg, noticed white Mississippians’ defiant posture when he traveled through the state months after the war.

“Wherever I go—the street, the shop, the house, or the steamboat—I hear the people talk in such a way as to indicate that they are yet unable to conceive of the Negro as possessing any rights at all.” Thomas worried that whites “who are honorable in their dealings with their white neighbors will cheat a Negro without feeling a single twinge of their honor. To kill a Negro they do not deem murder.” Such men openly boasted to Thomas that blacks “will catch hell” when local whites re-acquired political control. Trying to explain this defiance, Thomas pointed to prejudices seared into white minds and hearts during the era of slavery. As Thomas put it, though white Mississippians “admit that the individual relations of masters and slaves have been destroyed by the war and the President's emancipation proclamation, they still have an ingrained feeling that the blacks at large belong to the whites at large.”

In 1865 this deep prejudice appeared in Mississippi’s notorious Black Codes enacted in late November by the newly elected Mississippi Legislature. One of the first necessities of Reconstruction was to define the legal status of former slaves. How would Mississippi define citizenship? Which civil rights would the state legislators give to freedmen? Instead of embracing change Mississippi passed the first and most extreme Black Codes, laws meant to replicate slavery as much as possible. The codes used “vagrancy” laws to control the traffic of black people and punished them for any breach of Old South etiquette. Blacks could not be idle, disorderly, or use “insulting” gestures. Blacks could not own a gun or preach the Gospel without first receiving a special license. Black children were forced to work as “apprentices” for white planters, usually their former masters, until they turned eighteen. Most blatant of all, the state penal codes simply replaced the word “slave” with “freedman;” all the crimes and penalties for slaves were “in full force” for the emancipated.

On one level, the Black Codes made a political statement. White Mississippians meant to limit the political power of blacks by denying them civil rights. On another, deeper level, these codes revealed an economic struggle between former masters and freed slaves. Ex-masters wanted to force blacks to work as they had during bondage. Freedmen desired something else. They sought land to rent or own; they wanted self-sufficiency and independence from the old ways of plantation agriculture. Though most blacks wanted physical and economic distance from their terrible past, few achieved this goal. Blacks who saved money to purchase land seldom found a white man who would sell it to them. In parts of Mississippi when blacks offered to purchase land at $10 an acre, landowners refused and then sold the property to whites for half that price.

This white defiance had unintended consequences. Declining land prices and a failing cotton market threatened the livelihood of white planters. Proud men who had withstood wartime destruction and postwar uncertainties faced spiraling debt. Over 150 planters near Natchez, one of the wealthiest cotton regions in the world, forfeited their land to pay debts or back taxes. Something had to give. In time, when neither whites nor blacks could achieve their economic aims, landowners and laborers compromised by creating the sharecropping system. Planters provided land, animals, seed, and fertilizer; freedmen provided labor. They split the crop. This was hardly an ideal arrangement, but it resolved an economic impasse between land and labor, white and black. Former masters were guaranteed a constant source of labor, and former slaves could work a separate plot of earth, though they did not own it.

Radical Reconstruction, 1867-1876

Testimony from officials like Thomas and the oppressive Black Codes convinced Congress that Mississippi and other states needed a more thorough Reconstruction. Congressional, or Radical, Reconstruction ensued. In Mississippi this period contained great achievements and embarrassing failures. One of the greatest successes was black participation in democracy, both as voters and office holders. At least 226 black Mississippians held public office during Reconstruction, compared to only 46 blacks in Arkansas and 20 in Tennessee. Mississippi sent the first two (and only) black senators of this period to Congress. The first senator, Hiram R. Revels (1827-1901), was a free black from North Carolina who served as a chaplain to black troops during the Civil War. Revels moved to Natchez in 1866 and founded schools for freedmen throughout the South. The second African-American senator was Blanche K. Bruce (1841-1898). Bruce’s parents were a Virginia slave woman and her master. In Bolivar County, Mississippi, Bruce encouraged black political participation as the county sheriff, tax collector, and superintendent of education. This local political base catapulted Bruce to a U.S. Senate seat in 1875.

Other black and white Mississippians promoted a biracial political society. Former slave owner James Lusk Alcorn showed that not all white planters opposed progress. Alcorn created a political constituency that included northern Republicans who moved to the state, derisively called “carpetbaggers,” other white Mississippians who favored change, derisively called “scalawags,” and black Republicans, like James D. Lynch, Mississippi’s secretary of state.

But Radical Reconstruction infuriated southerners committed to white supremacy. As Republicans implemented political equality, terrorist groups used intimidation and violence to halt progress. The foremost of these organizations was the Ku Klux Klan. Established in Tennessee in 1866, the Klan became a violent paramilitary organization that often promoted planters’ interests and the Democratic Party. Klansmen hid beneath costumes meant to represent the ghosts of Confederate soldiers, but they often unmasked themselves when committing violence. This act sent a chilling message to their victims: Klansmen thought they could murder with impunity, because local authorities were unwilling or unable to stop them. The Klan targeted Republicans, “outspoken” blacks, and workers who challenged planter rule. In Monroe County, Klansmen killed black Mississippian Jack Dupree in front of his wife. The Klan targeted Dupree because he led a local Republican Party group and spoke his mind. Throughout Mississippi the Klan also sought to uphold planter authority by disciplining troublesome workers. Klansmen whipped a black woman for “laziness,” and pummeled a freedman for legally suing a white man. The terrorists told him that “darkeys were through with suing white men.” Mississippi courts, black churches, and schools became frequent targets of racial violence. In Meridian three black leaders were arrested in 1871 for making “incendiary” speeches. During the black men’s trial, Klansmen shot up the courtroom, killing the Republican judge and two defendants. The violence sparked a bloodbath in Meridian; white rioters picked out dozens of black leaders and murdered them in cold blood.

In time these violent tactics ruined democracy in Mississippi and throughout the South. In Vicksburg, white supremacists formed the White Man’s party, patrolled the streets with guns, and convinced black voters to stay home on election day. Their insurgency worked; Democratic candidates committed to white supremacy replaced every Republican incumbent in the 1875 elections. After this success, insurgents used violence and voter fraud to gain political control of the state. When the federal government refused to address these crimes, John R. Lynch, Mississippi’s Republican congressman, warned that “the war was fought in vain.” If all men were not equal before the law, America had not advanced very far since the Civil War. One hundred years later, the civil rights movement achieved the freedom that Lynch and thousands of other Mississippians first won and then lost during Reconstruction. For Lynch and his fellow Mississippians, these tumultuous postwar years were the best of times and the worst of times.

Jason Phillips, Ph.D., is assistant professor of history at Mississippi State University.

Posted May 2006

References:

Busbee, Jr., Westley F. Mississippi: A History. Wheeling, Illinois: Harlan Davidson, 2005, pp. 148-163.

Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution 1863-1877. New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1988.

Kolchin, Peter. A Sphinx on the American Land: The Nineteenth-Century South in Comparative Perspective. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2003.

Samuel Thomas, Testimony Before Congress, 1865, placed online by Stephen Mintz at the University of Houston at http://chnm.gmu.edu/ courses/122/recon/thomas.htm (accessed April 2006)

RECONSTRUCTION

By Howard Zinn

'In the year 1877, the signals were given for the rest of the century: the black would be put back; the strikes of white workers would not be tolerated; the industrial and political elites of North and South would take hold of the country and organize the greatest march of economic growth in human history. They would do it with the aid of, and at the expense of, black labor, white labor, Chinese labor, European immigrant labor, female labor, rewarding them differently by race, sex, national origin, and social class, in such a way as to create separate levels of oppression - a skillful terracing to stabilize the pyramid of wealth.'

Excerpt from: A People's History of the United States

LYNCHINGS, JIM CROW, FORCED LABOR

Ku Klux Klan, lynching, Ohio

Content in progress

US Government-sanctioned mass violence

Desperate to preserve slavery as a state-sanctioned labour system, the following acts expanded slavery to all territories under US control. All of them meant that even the freedom of thousands of free blacks in states and territories that had outlawed slavery could be in jeopardy.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, which required officials to report and capture runaway slaves to authorities anywhere in the United States.

The Missouri Compromise (1819)

The Compromise of 1850

The Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854)

The Supreme Court's Dred Scott decision (1857)

Reconstruction

Books, Article and Blog

Books:

- Black Reconstruction (Philadelphia, 1935), W.E.B.DuBois

- Stony The Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Jim Crow, Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

- Dark Sky Rising: Reconstruction and the Dawn of Jim Crow, Henry Louis Gates and Tonya Bolden

- Democracy in Black: How Race Still Enslaves the American Soul, 2016, Eddie S. Glaude Jr.

- Sweet Taste of Liberty: A True Story of Slavery and Restitution in America, 2019, W. Caleb McDaniel [Pulitzer Prize for History]

- Sweet Taste of Liberty: A True Story of Slavery and Restitution in America, 2019, W. Caleb McDaniel [Winner of the 2020 Pulitzer Prize in History]

- The Negro in Virginia, 1940, Compiled by the Workers of the Virginia Writers' Program (VWP) of the Works Progress Administration's Federal Writer's Project (FWP), Copyright 1994 by John F. Blair, Publisher, Winston-Salem, North Carolina

- A People's History of the United States, 1980, Howard Zinn

- Wilmington's Lie: The Murderous Coup of 1898 and the Rise of White Supremacy, 2020, David Zucchino (Winner of the 2021 Pulitzer Prize)

Blog:

- By Patrick Young, The Reconstruction Era, https://thereconstructionera.com/welcome-to-the-reconstruction-era-blog/#comments

Article:

- Civil rights icon Ruby Bridges thanks US Marshal who protected her so she could attend all-white school in 1960. September 6, 2013, The Daily Mail, UK, https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2413509/Civil-rights-icon-Ruby-Bridges-thanks-US-Marshal-protected-attend-white-school-1960.html

- The Murder of Ted Smith in1908, Princeton University, Firestone Library, https://graphicarts.princeton.edu/2018/05/03/the-murder-of-ted-smith-in-1908/

- [Emphasis Mine] By Jim Burroway, http://jimburroway.com/2019/08/28/postscards-and-souvenirs-from-center-texas/

- NPR Book reviews - In Stony The road, Henry Louis Gates Jr. Looks At The Period After Reconstruction, https://www.npr.org/2019/04/03/709462439/in-stony-the-road-henry-louis-gates-jr-looks-at-the-period-after-reconstruction

Detail of US History (forgotten).

Oil on canvas and mixed media.